As part of my teacher training in computer science education, I designed and conducted a one-day workshop aimed at students in grades 7 to 9. The goal of the workshop was to provide a hands-on introduction to 3D printing and digital modeling while deliberately focusing on computational and informatic ways of thinking, rather than on software operation alone.

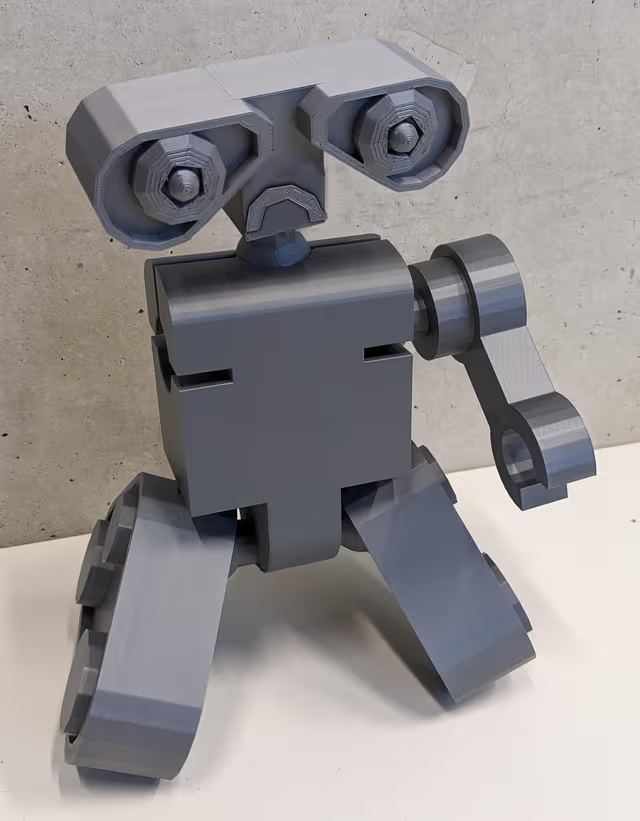

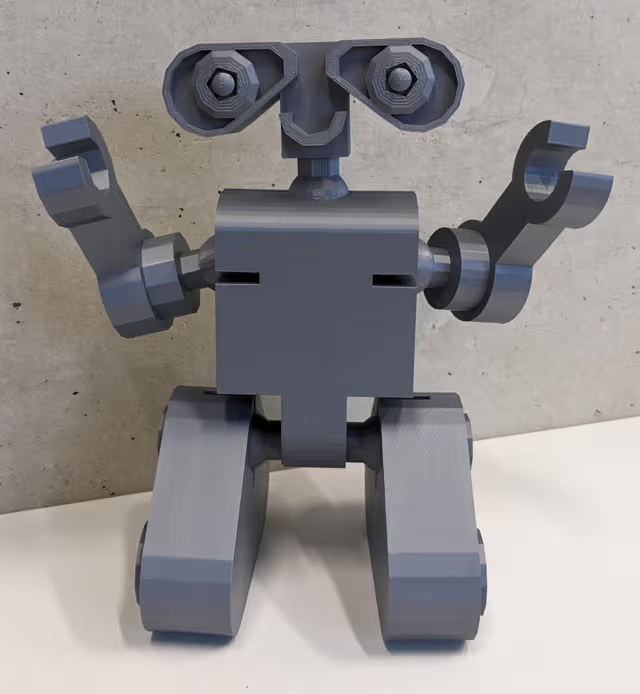

For this purpose, I designed a modular 3D robot in advance. The robot consisted of individual components and featured movable joints, allowing it to be assembled and disassembled in different ways. This modular structure was a deliberate didactic choice: it reflects the fundamental computer science principle of breaking down complex systems into manageable parts, and it conceptually prepared students for the later modeling task.

Narrative framing and problem orientation

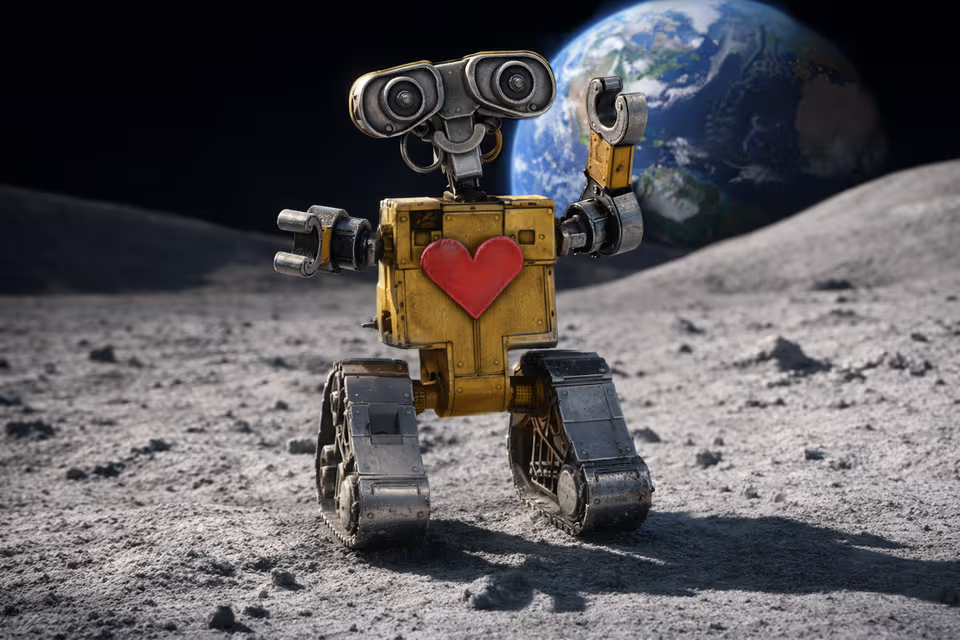

The workshop began with a narrative framing: students were introduced to the problem that the robot’s arm was broken and needed to be repaired. This scenario was supported by a short video clip from the film Wall-E, in which the robot loses an arm.

From a didactic perspective, this framing served several purposes. Narrative and film-based introductions are known to be highly motivating, and they help establish a clear, problem-oriented learning goal. Rather than learning abstract techniques, students worked toward a concrete objective: repairing the robot.

At the same time, the scenario highlighted one of the key societal opportunities of 3D printing: the cost-effective repair of products, which can increase maintainability and extend the lifespan of devices. In this way, the workshop connected technical learning with a real-world and sustainability-related context.

Haptic learning and multiple representations

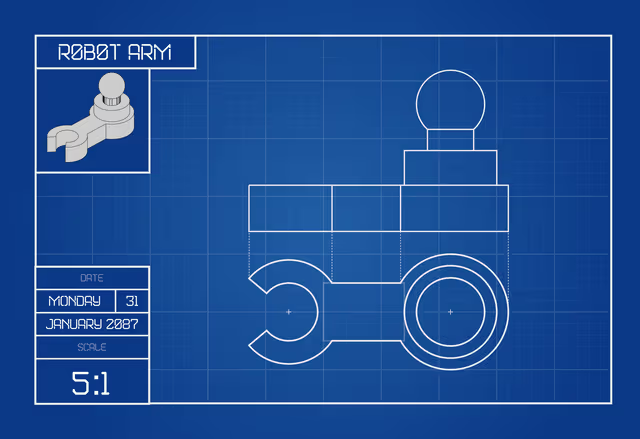

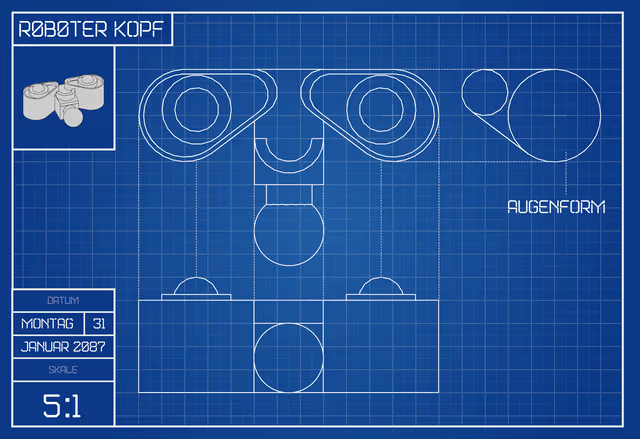

Each student received a small version of the robot with a missing arm. In addition, a large-scale model (10:1) was available as a shared reference. These physical objects were intentionally included to support enactive learning: learning through direct interaction with tangible artifacts. I also prepared blueprints that were to be used for the modelling process by the students.

Throughout the workshop, students worked across multiple levels of representation:

- the real object (the physical robot),

- an iconic representation (printed blueprints),

- and a symbolic representation (the digital model in BlocksCAD).

This progression supports understanding, especially for heterogeneous learner groups, and aligns with well-established representation models by Jerome Bruner.

Software choice and cognitive load reduction

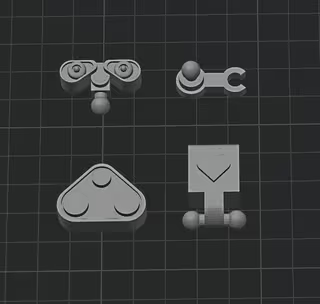

For digital modeling, I chose BlocksCAD instead of a text-based CAD tool. This decision was made to reduce extraneous cognitive load caused by syntax and complex interfaces, allowing students to concentrate on problem-solving and modeling concepts instead.

In the first phase of the workshop, students were introduced to the basics of 3D printing and the software environment.

They then learned about primitive shapes, structural decomposition, and set operations (union, difference, intersection). These concepts convey modularization as a core principle of computer science and provide the conceptual foundation needed to achieve the workshop’s main goal.

Cognitive activation instead of step-by-step imitation

A central didactic objective of the workshop was cognitive activation, which is widely regarded as a key characteristic of high-quality instruction. Rather than following predefined instructions or copying given dimensions, students were required to measure dimensions themselves using blueprints or the physical model make assumptions about proportions and geometry iteratively test and refine their digital models.

This approach encouraged students to make independent decisions, reflect on their assumptions, and actively validate their solutions. In this way, 3D printing became a medium for thinking rather than an end in itself.

The goal: repairing and customizing the robot

The primary goal of the workshop was to “repair” the robot by digitally modeling the missing arm and, when time permitted, printing it on-site. Students were allowed to take their printed parts home, which further increased motivation and a sense of ownership.

To support differentiation, more advanced students could alternatively model the robot’s head, a significantly more complex component. This open task structure helped address varying skill levels and prevented both under- and over-challenging students.

Scaffolding and gradual release of responsibility

The support structure of the workshop was carefully designed. At the beginning, students worked with substantial guidance to become familiar with the tools and concepts. During the modeling phase, this support was adapted to individual needs and gradually reduced.

This approach is known as scaffolding: learners are initially supported and then progressively empowered to solve problems independently. In a final open phase, students were free to design additional robot parts or entirely new components, such as alternative heads or custom modules.

Modeling, validation, and iteration

One of the distinctive didactic strengths of 3D printing is that it makes modeling as an iterative process tangible. Students experienced firsthand that models rarely work perfectly on the first attempt and must be tested, evaluated, and refined.

This understanding of modeling plays a central role in both mathematics education (modeling real-world situations) and computer science education (abstraction, formalization, and validation). The workshop therefore offered an interdisciplinary learning experience that fostered both problem-solving skills and abstract thinking.

Download the Model

The materials used in the workshop (the modular robot model, the digital blueprints, and the BlocksCAD files) are freely available for download. Educators and students can access and adapt these resources via the following link: